We need an open public competition to update our national monuments, remove imperial injustice and celebrate a new generation of diverse heroes write Nick Robins and Andrew Simms

The brutal death of George Floyd has triggered revulsion across the world, stimulating intense discussion not just on today’s problems of racial injustice, but also on its deep-seated historical roots. This has been dramatically illustrated in Bristol by the recent removal of the statue of the slave-trader, Edward Colston, by protestors and its unceremonious dumping in the city’s harbour. For historian David Olusoga, “this was not an attack on history. This is history – one of those rare historic moments whose arrival means that things can never go back to how they were.”

Statues signal what societies believe is praiseworthy, presenting to the public those who deserve to be known as heroes

Statues, of course, are not important in themselves, certainly when compared with the daily problems many people of colour face in the USA and the UK, as well as the lasting legacy of empire across the developing world. But statues do signal what societies believe is praiseworthy, presenting to the public those who deserve to be known as heroes. What is striking about the imperial statues that many are now calling to be removed is that these were rarely erected during the lifetime of the person concerned. In Bristol, Edward Colston’s statue was put up in 1895, 174 years after his death.

The most hated man in England

At the heart of government in London stands Robert Clive, the East India Company executive who conquered Bengal, became a symbol of corporate corruption and laid the foundations for the ‘great famine’ of 1769. When he committed suicide in nearby Berkeley Square in 1774, he was perhaps the most hated man in England according to his biographer. At the time, Dr Samuel Johnson wrote that he “had acquired his fortune by such crimes that his consciousness of them impelled him to cut his own throat”.

Our views of what is valued and heroic evolve – and so should their representation in our shared public spaces

So why does the greatest corporate rogue in British history stand, pride of place outside the Foreign Office? He’s hardly the best representative of Britain to the rest of the world. It all goes back to the early 20th century, when the British Empire needed a morale boost as campaigns for freedom grew. In this new mood of jingoism, the Viceroy of India Lord Curzon wanted to rehabilitate Clive as part of the 150th anniversary of his victory at the battle of Plassey in 1757. Not everyone was convinced. The Liberal Secretary of State for India, John Morley, argued that it would have been better if Clive had not won the battle and suggested a memorial to the Italian patriot Garibaldi instead. But Curzon raised the funds and got his way, and the statue was hoisted into place in 1911, with a twin going up in Calcutta. More than anything, perhaps, it marks the point of inevitable imperial decline. Just under four decades later in 1947, India won independence against the fearsome opposition of the British establishment, not least from Winston Churchill.

Revaluing what is heroic

Our views of what is valued and heroic evolve – and so should their representation in our shared public spaces. COVID19 has taught us powerfully that we give woefully insufficient ethical and financial recognition to our key workers in care and medicine, in retail, transport, food processing and manufacturing. When I wrote The Corporation that Changed the World about the East India Company earlier this century, I concluded that “removing Clive to a museum would help to finally mark an end to one part of the culture of empire.”

The Black Lives Matter protests have made many realise that it is high time for Clive’s statue to go. Robert Shrimsley, for example, writing in the Financial Times for example, states that “it isn’t hard to argue that he would be better situated, say, in the Imperial War Museum and that British diplomacy might find a worthier figurehead.”

Falling dominoes

The efforts to reassess and remove monuments that glorify imperial injustice are now gathering momentum. In London, a statue to another slave-trader, Robert Milligan, was removed peacefully just days after the protest in Bristol. London’s Mayor, Sadiq Khan has also established a new commission to review and improve diversity across the city’s landmarks. Pressure is mounting once more for the figure of Cecil Rhodes to be removed from the front of Oriel College, Oxford.

How democratic, refreshing and reuniting it could be to have a new wave of such public art to enjoy in the open air in these physically distanced times.

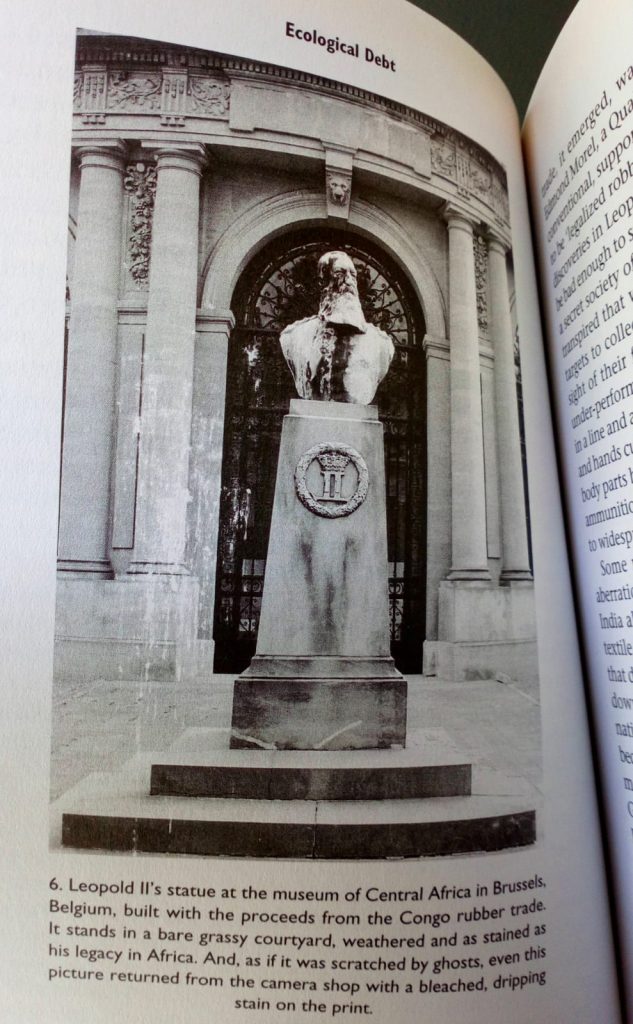

Clearly, this is an issue of global significance. In Belgium, for example, the focus is on King Leopold II, whose vicious colonial rule led to genocide in the Congo. There are multiple statues of him across the country, including at the Museum of Central Africa outside Brussels, built with the proceeds of the murderous colonial trade in rubber. After a full renovation the museum opened again in 2018 with Leopold’s statue still in place, and a pavilion named after the explorer Stanley, employed by Leopold, who said once in his writings that he had ‘hurled himself down the Congo like a hurricane, shooting down terrified natives left and right’. In Antwerp, one statue has already been taken down after protests and over 60,000 people have called for the statues across Brussels to be removed.

Ecological Debt: Global Warming & the Wealth of Nations

Opening up the conversation

Bristol agonised for years about the fate of Colston’s statue; the failure to come to a conclusion planted the seeds for it being toppled in protest. The London Mayor’s initiative is welcome, but it will have to lead to real action to avoid similar disappointments.

An open public competition to update our monuments would create a national conversation from which we could all learn important lessons and increase our awareness of both recent and more distant history. It could find a new generation of diverse global heroes, Britons and others, who best project the UK’s desire to fight injustice, promote freedom and work together to tackle common crises of our time, whether COVID19 or the climate crisis. There could be plinths a plenty available across London and other cities as obsolete monuments are shuffled off into the museums where they now belong.

How democratic, refreshing and reuniting it could be to have a new wave of such public art to enjoy in the open air in these physically distanced times.

Nick Robins is a historian diverted into the world of finance and sustainability by the climate crisis. Since 2018, he has been Professor in Practice for Sustainable Finance at the London School of Economics. He has published widely on sustainability issues (including Sustainable Investing: the Art of Long-term Performance). But his real passion is rethinking the past and in 2006 published The Corporation that Changed the World: How the East India Company Shaped the Modern Multinational; he is currently exploring the climate history of southern England. Twitter: @nvjrobins1

Andrew Simms is a co-director of the New Weather Institute, coordinator of the Rapid Transition Alliance, a research fellow at the University of Sussex and an author of several books including Ecological Debt: Global Warming & the Wealth of Nations (2nd ed 2009).